Putting workers and good jobs at the centre of the clean energy transition

Prospect energy researcher Thomas Weston looks at the role that our energy system must play in tackling the climate crisis and reveals what our energy members are telling us about the challenges we face in decarbonising our economy.

In a related article, he also reports from New York on the work being done in this area by campaigners and trade union colleagues in the USA, and how Prospect, with the launch of Climate Jobs UK, is also working to ensure that workers over here are not left behind by the clean energy revolution.

Sharing knowledge from New York on creating good climate jobs

The need for action to tackle climate change has never been more apparent. The 2015 Paris agreement set a target of limiting global warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels, but scientists are warning that level could quickly be breached. The impacts of climate change are global, and increasingly evident here in the UK.

As well as being a challenge for the population at large, climate change presents major challenges for workers, who face significant health risks when working in high temperatures. To protect workers, therefore, we need a new framework for managing work when temperatures rise to unsafe levels.

Most importantly though, we need to tackle the underlying cause of the crisis: greenhouse gas emissions. The UK economy, alongside all other major industrial economies around the world, has long been powered by fossil fuels, but this needs to change if we are to reduce our emissions to Net Zero and prevent the UK contributing further to global warming.

A successful transition away from fossil fuels is possible, but the transition will require a vast amount of investment in clean technologies and infrastructure, and this presents major economic opportunities.

However, the transition also contains major risks, as there are large numbers of workers whose livelihoods are based on carbon-intensive forms of production, with numerous communities up and down the country currently dependent on the economic lifeline that carbon-intensive industry provides.

Therefore, if the transition is to be successful, it needs to be carefully managed. The risks need to be minimised, and the opportunities need to be maximised.

Ensuring a just transition

We have some building blocks for a successful transition in place. The National Energy System Operator is in the process of setting out detailed plans for what the UK energy system should look like by 2050 and outlining pathways to getting there.

The Final Investment Decision for Sizewell C and the announcement of a Small Modular Reactor programme were important steps for the securing the future of the UK’s nuclear industry, which is due to play a vital role in a decarbonised power system.

The establishment of GB Energy and the National Wealth Fund have the potential to direct clean energy investment towards the technologies and the regions that need it most.

However, while all these things are welcome, we still do not have all the structures and policies in place that we need to ensure that vulnerable workers and communities are adequately supported and forthcoming investment results in large numbers of good jobs, with good pay, terms and conditions.

Prospect survey

Prospect recently conducted a survey of its members in the energy sector, and the results highlighted some major challenges associated with the transition.

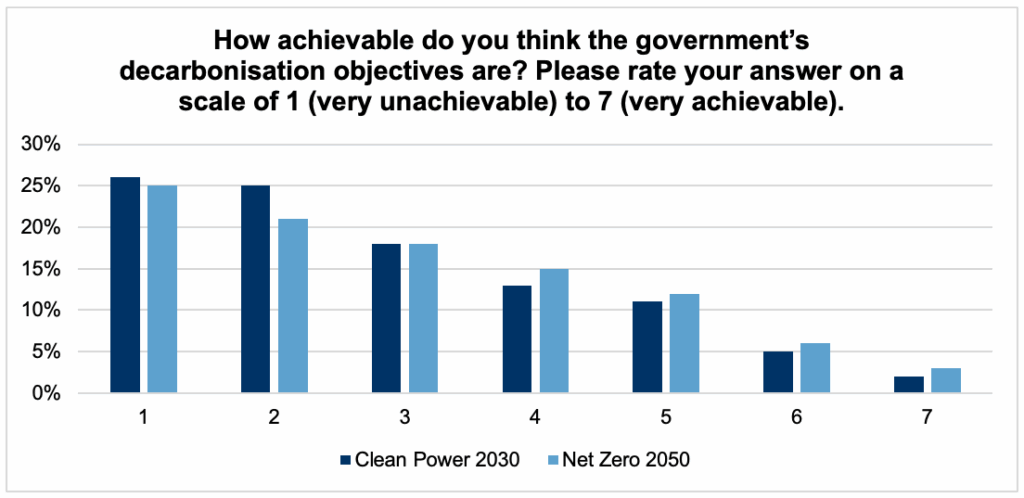

At a general level, there was strong support for the government’s decarbonisation objectives (81% support for decarbonising the power sector and 76% for decarbonising the whole economy) and this support was broadly consistent across all parts of the energy sector, however, there was major scepticism regarding their achievability.

Underpinning this was the issues of skills shortages and insufficient support and direction from government, with respondents rating these as the most likely barriers to achieving both Clean Power 2030 and Net Zero 2050.

Respondents repeatedly highlighted how their employers work within the framework set out by government, and there needs to be strong incentives in place for these companies if they are to work effectively to help the government achieve its decarbonisation objectives.

Skills and staffing

The issue of skills and staff shortages was consistently highlighted as an example of the problems with the current framework.

There is going to be a massive need for skilled workers in the sector over the coming years if the transition is to progress, but many employers in the sector have been holding back in making the necessary investments, with headcounts even reduced in certain areas.

The reasons behind this are varied, with respondents citing, among others, the following causes:

- Demands from the regulator, Ofgem, for greater ‘efficiencies’;

- Employers deliberately holding down headcount to reduce costs, with profit prioritised over broader strategic objectives;

- Insufficient certainty provided by the government about the nature and speed of the transition.

The cause varies depending on the employer and the part of the energy sector they operate in; in many cases there are multiple causes (included others not mentioned above.)

However, the ultimate solution is essentially the same: we need the government to be leading the way on the transition.

In many areas, it needs to be stepping up and making investments itself, and where it is relying on the private sector, it needs to create strong incentive structures to ensure that companies are working in line with the government’s strategic objectives.

Electricity networks

Electricity networks are due to play a central role in a decarbonised economy, and there should be tens of thousands good jobs that result from the reinforcement and expansion of the network over the coming years and decades.

However, respondents working in electricity network companies reported being under extreme and increasing pressure in terms of the day-to-day demands of their job, with worrying levels of stress and fatigue reported.

Many remarked on how headcounts had been held down in recent years and that there were now too few workers to staff basic maintenance work, let alone to train the tens of thousands of workers that are need to be recruited if current investment plans are to be achieved.

Clean generation

The transition will also require a massive buildout of clean generation capacity, as well as major investment to support the decarbonisation of heavy industry and home heating.

This will in part rely on older and more established technologies (e.g. nuclear power) but also newer and less well-established technologies (e.g. hydrogen). However, similar issues pertain for both.

Nuclear

Nuclear is a long-established part of the UK energy landscape, but the lack of investment and new projects over recent decades mean that we do not have the kind of skills base and pipeline we need as new projects get built and come online.

Many survey respondents for the nuclear sector highlighted the skewed age-profile of the workforce and how significant amounts of skills and expertise were being lost each year due to retirements.

For newer subsectors, there is also a major skills challenge, but the need for government intervention is, if anything, even greater, as the workforce is having to be built up from an even lower base and effective business models and regulatory frameworks are yet to be established.

Respondents working in emerging, or less developed, subsectors (e.g. hydrogen, carbon capture, usage and storage, onshore wind) were, therefore, some of the most likely to cite lack of support and direction from government as a barrier.

Fusion

An interesting exception to this trend was nuclear fusion.

In spite of the technology not yet being commercially viable, respondents working in this area were the most optimistic about the achievability of Net Zero and the least likely to be concerned about a lack of direction and support from government.

It is easy to understand why this might be. In contrast to other emerging subsectors:

- fusion has an identifiable public organisation responsible for its development (the UK Atomic Energy Authority);

- there is a clear long-term mission in place (demonstrating the feasibility of fusion by building an operational prototype fusion reactor by 2040);

- there is significant funding in place to support progress towards that mission (£2.5bn over the next five years.)

Like other subsectors, respondents working in fusion were concerned about skills shortages, but as a result of a recently announced funding package and long-term mission certainty, UKAEA is now collaborating with local authorities to develop training programmes, which will help provide for its anticipated skills requirements over the coming decades.

The challenge with fusion is unique compared to other clean energy technologies, and the interventions required to effectively drive the transition will be different for different energy subsectors.

However, there is a basic truth while holds across the wider clean energy landscape: There are tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of good, skilled jobs that could be created domestically as part of the clean energy transition, but only if the government makes strong interventions to:

A) improve job quality and establish effective training pathways for existing subsectors which are due to expand as part of the transition (e.g. networks and nuclear);

B) support the development and commercialisation of new technologies and effectively incentivise the domestication of their supply chains, making all policy support provided conditional on the creation of good, unionised jobs.

Prospect has long advocated for these kinds of interventions and we are committed to working with government to get them implemented; the success of the transition depends on it.

Read the second article from our energy researcher Thomas Weston, where he reports from New York on the work being done in this area by campaigners and trade union colleagues in the USA, and how Prospect, with the launch of Climate Jobs UK, is also working to ensure that workers over here are not left behind by the clean energy revolution.

Sharing knowledge from New York on creating good climate jobs